Why You Should Care About Black History

May 10, 2023

Black history education, whether it is found within a state-approved curriculum, or a compact heritage month poster, is crucial to understanding the current strife for representation and equality in America; here’s why you should care to learn more about it.

With the spike of gag order bills in school curricula and libraries in recent years that have an acute focus on racial discussions, teaching Black history has become an even larger necessity for American students to truly learn. Aside from being intertwined with the grassroots of American history, Black history is considered to be more of a worldly subject. But if it’s that vast on a global scale and within US history, is the current state of the history curriculum accurately representing all that it has to offer? Or rather, what constitutes a good representation of Black history in schools?

In February of this year, during Black History Month, Seton’s history teachers related their methods for teaching Black history within and outside of their curricula. As a result, this article will not only entertain why Black history is crucial for the average American education but focus on how Seton students can think about Black history inside and outside of class.

The curriculum’s tunnel vision

When we talk about NY state curricula there is, of course, an end-of-year test to dread and with it, a stockpile of at least some centuries of human history to unpack. When drudging through notes, students strategize and try to fit all they’ve learned into a neat satchel-like portion to then swallow. And what ends up taking precedence when trying to remember centuries of Black history is essentially the history of their oppression. That’s not exactly inaccurate. For US history, you see at least 400 years of oppression ranging from slavery to the Civil Rights Movement; for global history, there is a heavy emphasis, sprouting from the early stages of colonialism, on the drug and slave trades, principally paved by Europeans. As Mr. Jones, who teaches AP World and AP European history, says: “There’s no getting around the fact that centuries of our modern history after the Renaissance was dominated by colonialism and then imperialism afterwards.” There is also no getting around the fact that the history books are written by the colonizers and that by their effort to address said oppression, history curricula develop tunnel vision. That is, by featuring that aspect of Black history, the more neutral history is glossed over to prioritize themes like the slave trade and imperialism in Africa, or more in the case of US history, slavery, and the Civil Rights Movement.

It’s nothing ill-intentioned. Such themes come with the territory when teaching Black history, but with a state-mandated test emphasizing their role under the White, European’s thumb, it becomes increasingly difficult to teach Black history outside of the context of oppression. Mr. Phillips’ regents US history course, for example, “loves the themes of equality,” he says. And it should. The struggle for equal rights in the US carries through centuries of American history, even prior to its constitution, and onto present issues in today’s society. Consider this: Is it just common practice to prioritize some parts of a history over others, or is it a deliberate effort on the part of the curriculum?

Well, the issue isn’t what is prioritized, but rather what is ignored. But even within the history of oppression of Black people, even when limited to the US, there is an overabundance of material. Global studies teacher, Mr. McDonough says: “The thing is, if I taught every civil rights crime, it could take about four months, if not more… There’s just too much.” This is one of the reasons why a history curriculum might take a shortcut; to compensate for the vastness of the material by hyper-focusing on oppression. That doesn’t mean it’s taking a deliberate effort to “ignore” other aspects of Black history, but it does end up tipping the scale. With teaching the history of racism in America, for example, which is a behemoth to tackle, the curriculum is so eager to pack students with everything they need to know in time for the exam that they compromise by including 400 years of oppression in Black history, but teaching only ‘the basics.’

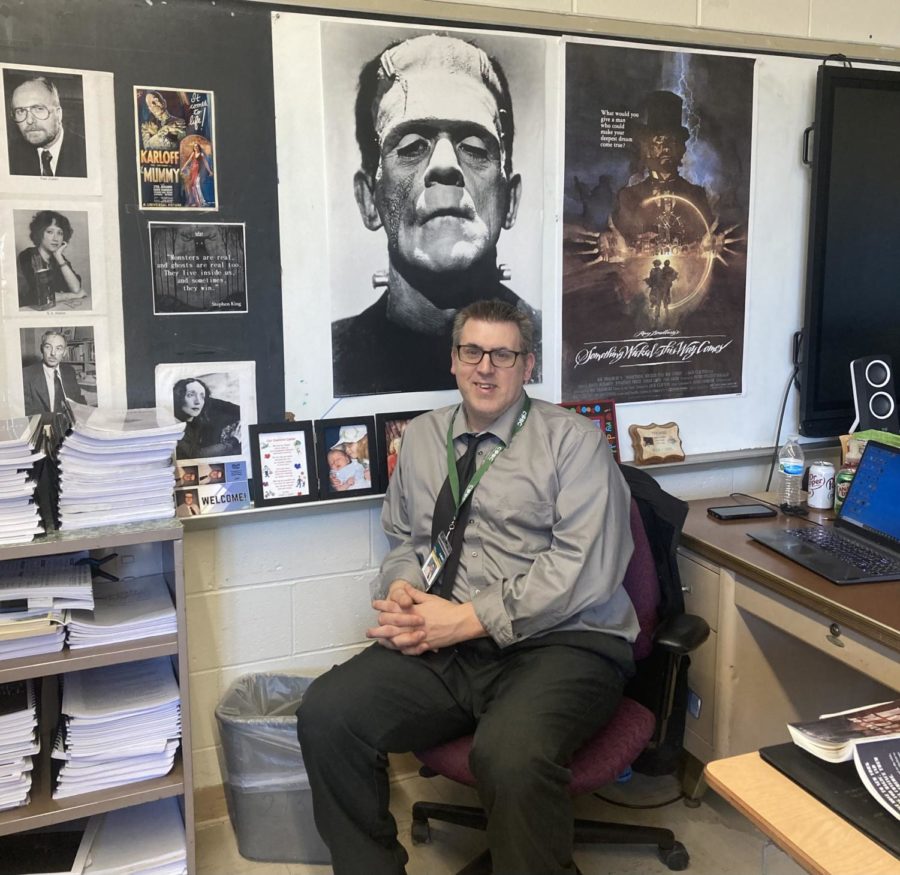

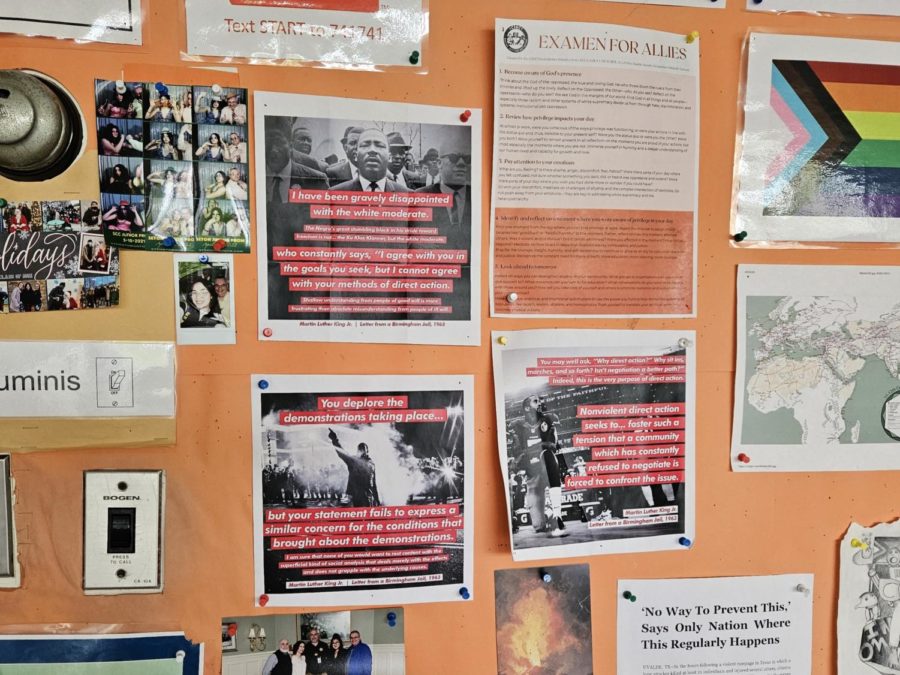

Any American student can confidently say they know who Martin Luther King is, but could the same apply for what he fought for? “I think it’s important to remember Martin Luther King, but not just the fact that he existed, but what he actually said,” Mr. Jones says. It seems obvious that one of the most prolific central figures of the Civil Rights Movement should be remembered for what he said, but oftentimes, excluding individual efforts to expand on the curriculum, history in a high school classroom is satisfied with skimming through such names because they are nationally recognized. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that King’s criticisms and teachings are carried on by the mere face value of his name, or that one picture of him leaning on a podium with his arm outstretched towards the public. Teachers and students alike have to take that extra step in actually understanding what fighting against racism meant 60 years ago in order to understand why we even hold conversations about racism today.

Teaching empathy

How do teachers encourage students to connect with the grittier parts of Black history? When it comes to making students face that part of their own history, especially when they don’t have any other source of exposure, teachers often have to veer off from a standardized curriculum. To “teach” empathy is not to dictate or lecture. It is to challenge students’ perspectives on subject matter that is simply harder to understand, or absorb compared to neutral history lessons. As already mentioned, there is a danger to teaching Black history through the sole lens of oppression because the curriculum, whether intentionally or not, dilutes the impact of Black history when discussed outside of a common theme of struggle. But there is also a danger to not emphasizing it.

In order for students to understand why learning about Black history is important, teachers have to unearth students’ empathetic ear. Not to pity, but to sympathize, while still acknowledging that there is a large gap of perspective to bridge between a classroom of private school students that are mostly white, and the experiences of say a slave, or a ‘freed’ slave under Jim Crow. “A great deal of these students haven’t been exposed to it, or not in the way you should cover it,” says Mr. McDonough.

Seton’s history teachers have adopted different methods for bridging the gap between a classroom and society’s deeply polarized, racist history. Mr. Phillips’ US history classes bear witness to the heroism of the oppressed who challenged their oppressors and sought freedom and equality. In addition to sharing the personal experiences of Black Americans, Mr. Phillips also shares his own experiences teaching in inner-city DC public schools, from which he hopes students will gain some perspective as he himself has. His personal favorite to revisit every year is the Little Rock Nine, which follows nine Black students that were entering Little Rock, Arkansas’ Central High School as its first-ever Black students following the Supreme Court ruling pledging to desegregate schools in the years prior in 1954. “We have to try to understand each other,” Mr. Phillips says. “Our struggles may be different, but we can all relate to anxiety, failure, rejection; it’s amazing what some of these figures were able to go through and then triumph as well.”

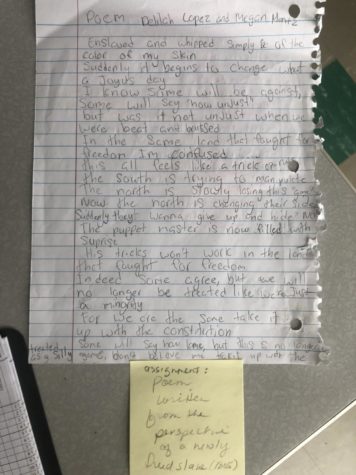

Mrs. Linge’s middle school US history classroom, just to list one example, assigns her middle schoolers a poetry assignment. Seton high school students may recognize this assignment from their time in the middle school hallway: to write a poem from the perspective of a newly freed slave. In turn, Seton middle schoolers are encouraged to interact with the material, instead of having anything that may help them remember a date and place better strategically honed and hammered in.

Written by 8th graders, Delilah Lopez and Megan Mentz

Mr. Jones is famous for his random Google searches. But they shouldn’t be considered to be at “random.” So, maybe they are better referred to as educational tangents. Behind the many side-histories and spontaneous routes his classes take on a daily basis, is the very clear intention to engage and challenge his students. For one: Martin Luther King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’ Considered to be King’s magnum opus thesis, the open letter details his many criticisms against an unjust justice system as well as his methodology for combating racism through direct action. And Mr. Jones consistently comes back to and refers to it in efforts to relate its absolute influence on the Civil Rights Movement and modern activism.

What any high school student that has taken one of Mr. McDonough’s Global Studies classes would be able to tell you about their time in his classroom is the movie Amistad. Directed by Steven Spielberg, Amistad centers on the legal status of Africans who rise up against their captors on the high seas as they are being transported through the Middle Passage and are brought to trial in a New England court. And while Mr. McDonough doesn’t show the entire movie, the clip that he does show recounts the bestiality of the slave trade as slaves are starved, beaten, and packed like sardines aboard slave ships. As he says: “When it’s right in your face, you cannot deny it.”

McDonough: ‘No one’s guilty for the crimes of someone in the past.’

One of the prevailing arguments for why racism should not be ‘taught’ in schools is that it would be distributing blame. The US history curriculum, for instance, is submerged in the history of slavery and segregation; it’s only reasonable to address the common denominator. You don’t have to admit guilt in order to seek change, or to question your education and society. That’s not what history is for. Surely anyone that has encountered a history teacher can repeat this phrase verbatim: ‘Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.’ Teaching Black history doesn’t turn students into potential targets, but into better future citizens. How else are students supposed to recognize racism in today’s world; within their own communities; in themselves? Young students that have yet to be formally introduced to adulthood should be expected to convert what they learn in a classroom setting into reality, and that is especially true when it comes to history.

The value and limitations of heritage months

“We don’t live in a world where people care about Black History Month.” Or, at least, not enough to use it as a resource instead of an annual reminder to buy a t-shirt. It should serve as a reminder to learn more about Black history, even if it is fleeting. With the celebration of heritage months becoming such a widely recognized opportunity for furthering discussions about education and representation, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that Black history, like any other history, can’t be easily summarized and posted on a pamphlet or flyer. Just the fact that we’ve begun to resort to such methods to popularize Black history should serve as an indicator of the need for a proper, in-depth education in classrooms. However, as this article has hopefully demonstrated, the solution to this dilemma is not exactly resolute.

So, why should you care about Black history? Simple: All the questions and issues addressed in this article barely skim the tip of the iceberg. Black history is a rare, untamed realm of education that is as relevant as it is complex, and its web-like nature only makes it harder to pin down. But it is because of this often overwhelming amount of material that teachers and students should feel even more enticed to learn more, and be challenged by its grandeur as well as its power.

![College of Community and Public Affairs graduates cheering during the CCPA Commencement Ceremony. [Via Daily Photos at binghamton.edu]](https://sccvoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Screenshot-2023-05-16-10.50.55-PM.png)