Now entering a post-pandemic ‘eye of the storm’ in education, elite colleges now find themselves unequipped to identify potential for success in students, especially those from different socioeconomic backgrounds, without standardized measures of selection.

Seemingly contrary to what the world of education has chosen to condemn, re-affirming research finds that standardized testing, particularly the SAT and ACT exams, may be the most reliable indicator of student achievement and success in college with relatively small gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. And elite colleges, those at the greatest extremes of academic excellence, who were at the forefront of the test optional initiative during the pandemic, are now facing the fall out of exempting applicants from submitting their SAT/ACT scores: it is becoming increasingly harder for admissions officers to distinguish between applicants who will likely thrive and those who will likely struggle as presumably excelling students.

However, if the research were as resolute and simple as that, why have most of the prominent institutions in American education turned themselves inside out to instead prioritize inconsistent and unrealistic admissions data? Alas, it is not. And the pandemic is just the tip of the iceberg.

Where does the persistent attitude against standardized testing come from?

It is difficult to say exactly when the climate in education shifted against standardized testing, but it is mostly clear why. In general, the professionals in the education field that have strayed from the standardized testing method are mostly concerned with the inequitable standards that it perpetuates and its supposed ineffectiveness in assessing students’ academic performance and potential. While these concerns are not unwarranted, they do prove to be invalid.

Even if misguided, there does exist a dark history associated with the SAT/ACT that is hard to ignore. Carl Brigham, the originator of the SAT test, was a known eugenicist. He believed the test would weed out the racial inferiority of those not from Nordic-white descent. In his thesis, A Study of American Intelligence, he writes that the SAT test would prove the racial superiority of white Americans and prevent “the continued propagation of defective strains in the present population”—chiefly, the “infiltration of white blood into the Negro.” Eventually though, Brigham would detract from his conclusions and admit that heredity by ethnic groups had little to do with average performance on the SAT; he would actually never participate in the national administration of the test, but rather, naturally oppose it. The modern usage for the SAT actually arises around WWII as the large increase in prospective college students, particularly veterans, begins to steer more into higher education. The SAT began to serve as a scholarship program for desirable borderline students from public schools that did not share the aristocratic ‘character’ of traditional, northeastern private students in order to diversify the elite. However, with the growing popularity and expansion of the SAT to the outermost edges of the country came a gradual decline in test scores, a reality the federal government struggled to cope with.

Failed federal initiatives to close this achievement gap would pave the way for America’s estranged relationship with standardized testing. During the 1980s, a report titled A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform convinced the nation that American students were lagging behind the rest of the global workforce in education. Its findings, which are disputed now, would influence bipartisan legislation in education reform in the following decades and cement public opinion on the state of the American school system; its crowning resolution: the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. The resolution envisioned to close the ever-widening education gap between the rich and the poor, English language learners, students with special needs, and minority children, requiring state schools to bring students to a proficiency level in reading and math by 2013. Unfortunately, it backfired. NCLB kept states on track towards their proficiency expectation by administering yearly progress assessments that were tied to a cascade of punitive damages, such as state intervention in the form of school shutdowns. The requirement introduced high-stakes testing as a national standard for proper education, tying performance to funding and success and prioritizing “drill and kill” test-taking strategies over deeper comprehension and exploration. Additionally, this severely fragmented the act’s proclamation of a combined effort towards padlocking the achievement gap as it allowed for state-independent enforcement of its standards. The reality is that the US is a bit of a scattered mess when it comes to establishing unity in education and that is precisely the reason why standardized testing originally captured the country and, ironically, why it’s gathered so much opposition.

The ambition to consolidate education in America has proved itself to be a doomed venture. And its failings have bred a lot of resentment and distrust within the American public and education system.

What does the data reveal?

One of the greatest misconceptions about standardized testing is that it has no merit in accurately assessing students’ capabilities and potential for success. In fact, it is the complete opposite. A test’s reliability hinges on its ability to produce consistent results; meaning that a person would not be able to receive significantly different scores on the same test no matter how many times they were to take it. In this way, the test is unbiased. However, other influences outside of the test’s control may introduce bias.

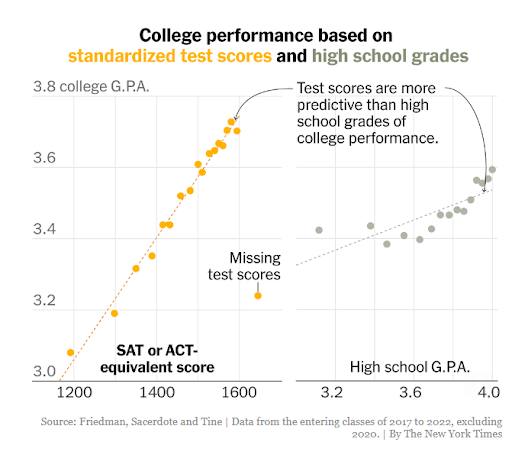

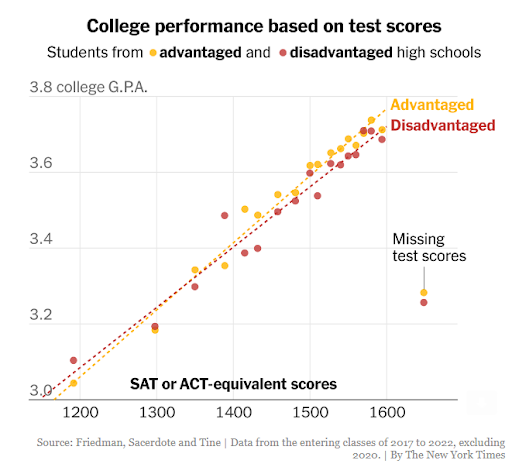

Keeping this in mind, the data reveals the following: 1) standardized test scores are a greater predictor of academic success or failure in college than high school grades; 2) high school grades are poorly correlated with college GPA; 3) there is no significant difference in college performance between students of advantaged high schools and students of disadvantaged high schools with similar SAT/ACT scores.

The New York Times (The Misguided War on Standardized Testing, Leonhardt, D.)

The New York Times (The Misguided War on Standardized Testing, Leonhardt, D.)

Yes, high school grades are not as telling and predictive of a student’s ability to thrive in college as previously thought. This is especially true for growing trends of grade inflation, but apart from that, your high school GPA naturally lacks something that the SAT/ACT is specifically designed to assess: cognitive potential. It measures a person’s ability to learn a new skill, or their potential to develop skills in specific areas. Knowing this, it is not surprising that high school grades are not as developed predictors of college success when compared to SAT/ACT scores. When graduating students enter college, they are faced with an array of unexplored subjects and varying degrees of difficulty that some are more adept at adjusting to than others. This is also why the controversy surrounding standardized testing mostly involves elite colleges. If a student that manages to get accepted into an Ivy League school solely based on their high school grades starts to struggle academically and eventually drops out, one might like to wonder why such a prestigious and selective school that holds its students to notoriously higher standards would suffer the opposite effect that its academic prowess expects. The gap between high school and college success becomes much more expressed.

It is also not surprising why many have chosen to disregard SAT/ACT scores as a reliable measure for success. They’re not the ones rising. An ACT report revealed that, on average, high school GPA increased 0.19 grade points from 3.17 in 2010 to 3.36 in 2021. The three-year period between 2018 and 2021 saw more grade inflation than in the preceding eight years, growing by 0.1 grade points, according to the report.

Comparatively, SAT/ACT scores have remained relatively stable throughout most of their history, with performance decline suddenly appearing in the early 2000s. In 2023, ACT scores have reached a 30-year record low, with SAT scores not falling far behind.

What standardized testing has been most recently accused of in the field of education is reinforcing inequitable measures for success. This is not completely untrue. The data also shows that there is a strong positive correlation between household income and SAT/ACT scores, much stronger than that between household income and GPA. In fact, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans were found to be 13 times more likely than the children of low-income families to score 1300 or higher on SAT/ACT tests. There are wealth disparities embedded in our education system that manifest in all aspects of college admissions. However, to invalidate standardized testing altogether is misguided and avoidant, and getting rid of the SAT/ACT requirement is not closing the wealth gap, but rather expanding it.

Not only did the data reveal that SAT/ACT scores are greater predictors of college success than high school GPA, it also indicates that the wealth disparity these standardized tests trend cannot be confused with their ability to accurately project which students will likely succeed or struggle in college, regardless of socioeconomic position. There is no evidence that students from higher-resourced backgrounds outperform students from lower-resourced backgrounds in college. It is likely that the primary factors realizing this wealth disparity in SAT/ACT scores are actually external and not intrinsic to the test itself. Meaning that an advantaged position may earn a greater percentage of students a leg up in scoring higher for the SAT/ACT, but once they enter college, that inequality is bridged between them and students from disadvantaged backgrounds with comparable scores. In fact, restricting the SAT/ACT has proved counterproductive in allowing students from disadvantaged backgrounds to encounter this balancing out.

A study published in late 2023 found large differences in application rates by parental income at public institutions, especially for out-of-state students. In early February, Dartmouth College announced that it would once again require applicants to resubmit standardized test scores specifically because they found their test-optional policy has actually discouraged many high-achieving, less-advantaged applicants from submitting scores even when doing so would allow admissions officers to identify them as students likely to succeed at Dartmouth and in turn benefit their application. The data indicates that getting rid of the SAT/ACT requirement, opposite to what the test-optional policy predicted, is restricting the available pool of eligible applicants to the country’s most privileged and advantaged, to those that can flood their college applications with qualifications unique to their affluence and connections. Research finds that 24% of the admissions advantage for students from top 1% families can be explained by the recruitment of athletes, who tend to come from higher-income families; 46% of the admissions advantage comes from preferential admission for students whose parents attended the same college (“legacies”); the remaining 31% of the admissions advantage for students from families in the top 1% is explained by the fact that they are judged to have stronger non-academic credentials than students from lower-income families.

Is standardized testing really the best option?

Well, it depends on the benchmark. It is more than fair to say that standardized testing does offer reliable, applicable data that schools can use to accurately survey students’ abilities and progress. The question here is not whether it does, but rather, what else is there? And what would it achieve?

There is the simple answer to this that many have grown accustomed to resorting to which is to get rid of standardized tests altogether and replace them with alternative methods of assessment focused on the evaluation of students solely for their improvement and development. This approach is much more concerned with a student’s individual fulfillment, rather than their performance, an idealistic, almost fairy tale-like, view that many in America have anchored to against the torrents of a lagging global performance as well as a national panic. But, again, it’s not that simple.

For example, probably the greatest success story for this approach in education, one that gravitates around any conversation regarding the education system in America that you will ever have, is Finland. However, comparing the two is likely equating an ant hill to a mountain range. While Finland has a majorly homogeneous population of 5.5 million, the US contains the largest immigrant population in the world and has a total population of over 300 million. This is why the data shows that even though Finland is ahead in academic achievement and rigor, it lags behind in providing equity in education between boys and girls and for immigrant students. While Finland’s teacher assessment method may expose its most marginalized students to cultural biases in an education system analogous to its available diversity, the US’s standardized testing method evidently controls for such biases in a country where inequalities are prevalent among one of the most diverse populations in the world.

![College of Community and Public Affairs graduates cheering during the CCPA Commencement Ceremony. [Via Daily Photos at binghamton.edu]](https://sccvoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Screenshot-2023-05-16-10.50.55-PM.png)